Carl Gustav Jung, a prominent Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, is best known for his profound contributions to psychology, particularly through his exploration of the collective unconscious and the concept of archetypes. Born on July 26, 1875, in Kesswil, Switzerland, Jung initially trained as a physician before delving into psychiatry. His collaboration with Sigmund Freud significantly shaped his early career; however, Jung eventually diverged from Freud’s theories to develop his own ideas about the psyche.

The Collective Unconscious

Sigmund Freud’s perspective primarily focused on the role of personal experiences and repressed memories in shaping an individual’s psyche. While he emphasized the importance of individual trauma and familial relationships in psychological development, Jung proposed that the collective unconscious is an inherited aspect of our psyche that transcends individual life experiences. He argued that this shared layer of unconsciousness contains universal symbols known as archetypes—such as the Hero, the Mother, and the Shadow—that manifest in myths, dreams, art, and religious practices worldwide.

These archetypes serve as fundamental building blocks for human thought and behavior, influencing how individuals perceive their world and interact with others. For instance, common narratives found in folklore or literature often reflect these archetypal themes, suggesting that they resonate deeply within our collective psyche. Jung believed that by exploring these archetypes through various forms of expression—be it through therapy, art, or cultural analysis—we can gain insights into both individual behavior and broader societal patterns.

Furthermore, Jung posited that the collective unconscious plays a crucial role in shaping cultural phenomena such as religion, mythology, and even modern psychology itself. By recognizing the existence of this shared unconscious layer, we can better understand not only our own motivations but also those of people from diverse backgrounds. In essence, Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious invites us to consider how interconnected we are as humans through shared symbols and experiences that transcend time and geography.

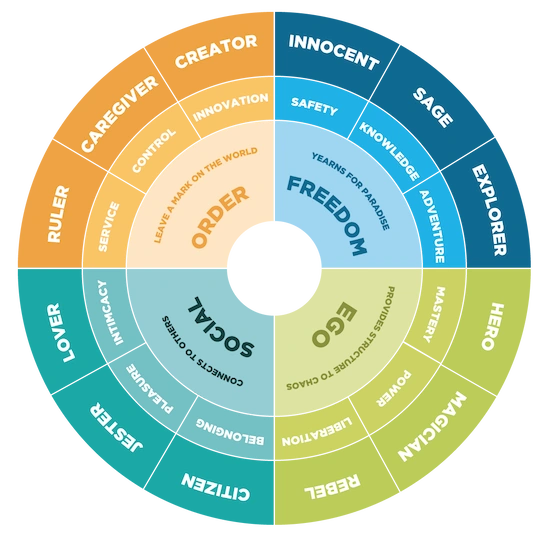

The 4 Cardinal Orientations

Carl Jung proposed four cardinal orientations that represent the range of basic human motivations. These orientations are: Ego, Order, Social, and Freedom. Each of these orientations is associated with specific archetypes that embody their core desires and goals.

1. Ego Orientation: The Ego orientation focuses on making one’s presence known and admired. The archetypes associated with this orientation are:

Hero, Magician, Rebel (or Outlaw).

2. Order Orientation: The Order orientation emphasizes maintaining structure in societal settings. The archetypes linked to this orientation include:

Caregiver, Ruler, Creator (or Artist).

3. Social Orientation: The Social orientation focuses on fostering genuine connections with others. The archetypes associated with this orientation are:

Lover, Jester, Citizen (or Everyman).

4. Freedom Orientation: The Freedom orientation emphasizes breaking free from physical and psychological limits. The archetypes related to this orientation include:

Innocent, Sage, Explorer.

These cardinal orientations provide a framework for understanding how each archetype operates within the context of human motivations, shaping individual behaviors and interactions with others.

The 12 Jungian Archetypes

Archetypes are defined as innate symbols or themes that recur universally across different cultures and historical periods. They represent fundamental human experiences and emotions, serving as templates for understanding life’s complexities. According to Jungian theory, these archetypes manifest in dreams, myths, art, literature, and religious practices.

Jung identified numerous archetypes but emphasized twelve primary ones that have significant implications in both psychology and storytelling. Each archetype embodies specific characteristics and motivations that resonate deeply within the human experience.

1. The Hero

The Hero archetype embodies courage, determination, and a relentless pursuit of self-improvement. Heroes are often depicted facing formidable challenges head-on; they embark on journeys that require them to confront obstacles or evil forces threatening their world or loved ones.

Historically speaking, heroes have been celebrated across cultures—from ancient Greek mythology with figures like Heracles to modern-day superheroes like Superman. These characters inspire others through their bravery while also grappling with personal vulnerabilities that make them relatable.

Joseph Campbell’s concept of the “Hero’s Journey” outlines a common narrative structure found in many myths and stories worldwide. This framework includes stages such as “the call to adventure”, “the ordeal”, and “the return”, illustrating how heroes grow through their experiences while ultimately striving for greater good.

Moreover, contemporary interpretations of heroism have expanded beyond traditional notions of physical strength or valor; emotional resilience and moral integrity are increasingly recognized as heroic traits in today’s narratives. For instance, characters like Atticus Finch from Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” exemplify moral courage in standing up against injustice despite societal pressures.

2. The Magician

The Magician archetype embodies transformation through knowledge or skillful manipulation of reality—often seen as visionaries who create change by harnessing unseen forces such as technology or magic in folklore. Throughout history, individuals like Leonardo da Vinci exemplified this archetype; he was not only an artist but also an inventor and scientist whose ideas were ahead of his time.

Magicians inspire wonder but risk becoming manipulative if misusing their power. In literature and mythology, figures such as Merlin from Arthurian legend represent the duality of this archetype—capable of great wisdom yet also prone to deception or manipulation for personal gain or greater good. In contemporary contexts, technologists and entrepreneurs often embody this archetype by leveraging innovation to disrupt industries but must navigate ethical considerations regarding their influence on society.

The rise of digital technology has amplified the Magician’s role in modern society; tech innovators like Steve Jobs transformed how we interact with technology while also raising questions about privacy, control, and ethical responsibility in wielding such transformative power.

3. The Rebel (or Outlaw)

The Rebel archetype represents defiance against authority or societal norms—a theme prevalent throughout history as individuals challenge conventions for change or self-expression. Figures such as Rosa Parks during the Civil Rights Movement, or Ernesto “Che” Guevara during the Cuban Revolution, represent two examples of how rebels can inspire transformation through nonconformity.

Rebels often emerge during times of social upheaval when existing structures are perceived as unjust or oppressive. Their actions can catalyze significant societal shifts; however, they may also encounter isolation or conflict due to their nonconformity. In literature and film, rebellious characters often serve as catalysts for change—think of Holden Caulfield from J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye”, whose disdain for societal expectations resonates with many readers grappling with identity.

Psychologically speaking, rebels may exhibit traits associated with low agreeableness and high assertiveness—qualities that enable them to stand against prevailing norms but may also lead them into conflict with authority figures or peers who uphold traditional values.

4. The Caregiver

The Caregiver archetype is deeply rooted in the human experience, often associated with figures who embody compassion, nurturing, and selflessness. Historically, caregivers have played crucial roles in various cultures, from the ancient matriarchs who managed family dynamics to modern-day healthcare professionals who dedicate their lives to the well-being of others. This archetype prioritizes the needs of others above their own, often seeking to protect those who are vulnerable—children, the elderly, or those facing hardship.

In literature and mythology, caregivers are frequently depicted as maternal figures or wise mentors. For instance, characters like Marmee from Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women” exemplify this archetype by providing emotional support and guidance to their families. However, while they embody love and support, caregivers may also experience burnout due to their self-sacrificing nature. The phenomenon of caregiver burnout is well-documented in psychological studies; it occurs when individuals neglect their own needs while focusing on others’, leading to physical and emotional exhaustion.

Moreover, the caregiver’s role can be seen across various professions—nurses, teachers, social workers—each contributing significantly to society’s fabric. Yet, despite their importance, caregivers often struggle with societal recognition and personal fulfillment. The balance between caring for others and attending to one’s own needs remains a critical challenge for many in this archetype.

5. The Ruler

The Ruler archetype represents leadership authority responsibility over others’ well-being within structured environments such as governments or organizations. Historical figures like Julius Caesar or Queen Elizabeth I exemplify this archetype by demonstrating strong leadership qualities that shaped nations during pivotal moments in history.

Rulers seek order stability while ensuring that everyone follows rules; however excessive control can lead them toward tyranny rather than benevolence. The balance between authority and freedom has been a recurring theme throughout history—from the absolute monarchies of the past to modern democratic systems where leaders are held accountable by their constituents.

In contemporary governance, leaders face challenges related to maintaining order while respecting individual freedoms—a delicate balance that can easily tip into authoritarianism if unchecked. The lessons learned from historical rulers serve as cautionary tales for modern leaders about the potential consequences of overreach in pursuit of stability.

6. The Creator (or Artist)

The Creator archetype embodies imagination, innovation, and artistic expression. Throughout history, Creators have been pivotal in driving cultural movements and technological advancements. Figures like Filippo Brunelleschi exemplify this archetype; he was famous not only for being a great architect, but also for developing important innovations such as linear perspective, which were ahead of his time.

Creativity manifests in various forms—be it through visual arts, literature, music, or scientific discovery. The Renaissance period marked a significant surge in creative expression as artists sought to explore human emotion and experience more profoundly than ever before. This era produced masterpieces that continue to influence modern art and thought.

Despite their strengths, Creators often grapple with perfectionism or fear of failure. This struggle can hinder their ability to produce work or share their ideas with the world. Research indicates that perfectionism can lead to anxiety and procrastination among creatives; they may become so focused on achieving an ideal outcome that they fail to complete projects altogether. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for fostering a healthy creative process.

7. The Lover

The Lover archetype is deeply rooted in the human experience of passion, intimacy, and connection with others. This archetype can be traced back to various cultural narratives and mythologies that celebrate love and beauty. For instance, in ancient Greek mythology, Aphrodite (or Venus in Roman mythology) represents love and beauty, embodying the essence of the Lover through her relationships and interactions with gods and mortals alike.

Historically, the Lover has been depicted in literature as a figure who seeks deep emotional fulfillment through romantic relationships. Shakespeare’s works often highlight this archetype; characters like Romeo from “Romeo and Juliet” epitomize the passionate pursuit of love, showcasing both its joys and its potential for tragedy. The Lover celebrates life’s pleasures—art, music, romance—and finds meaning in these experiences.

However, the shadow side of the Lover archetype emerges when individuals become overly dependent on relationships for validation. This dependency can lead to unhealthy attachments or co-dependency, where one’s self-worth is tied to their partner’s approval or affection. Psychological studies have shown that such dependencies can stem from early attachment styles formed during childhood, influencing how individuals relate to others throughout their lives.

8. The Jester

The Jester archetype represents humor, playfulness, and the ability to see life from a lighter perspective. Historically, jesters played important roles in royal courts as entertainers who used wit to challenge authority while providing comic relief during serious times. They often served as social commentators who could speak truths that others could not due to their position.

In literature and folklore, Jesters are often portrayed as wise fools—characters who use humor not just for entertainment but also for insight into human nature and societal norms. For example, Robin Williams was an engaging and extremely entertaining actor, who was also capable of using irony and sarcasm in a biting way, but at the same time possessed the typical dark side of the Jester figure.

While Jesters remind us not to take life too seriously by using humor as a coping mechanism for life’s challenges, they may also avoid confronting deeper issues by relying solely on comedy as a shield against vulnerability or pain. This avoidance can prevent meaningful connections with others or hinder personal growth.

9. The Citizen (or Everyman)

The Citizen, often referred to as the Everyman archetype, represents the average individual who embodies relatability, humility, and a desire for belonging. This archetype is characterized by its focus on connecting with others and valuing common experiences. The Everyman seeks to fit in with society and is often portrayed as down-to-earth, approachable, and genuine. The primary desire of the Everyman archetype is to connect with others and belong to a community. This need for connection drives their actions and motivations throughout various narratives.

The goal of the Everyman is to achieve a sense of belonging and acceptance within their social environment. Conversely, their greatest fear is being left out or standing out from the crowd, which can lead to feelings of isolation or alienation. To fulfill their core desire, the Everyman develops ordinary virtues such as empathy, realism, and sincerity. They strive to be relatable by embracing simplicity in their lives and interactions with others. While the Everyman archetype possesses many admirable traits, it also has weaknesses. One significant flaw is the potential loss of self-identity in an effort to blend in or maintain superficial relationships. This can lead to a lack of depth in personal connections.

In literature and media, characters embodying the Everyman archetype often find themselves thrust into extraordinary situations despite their ordinary backgrounds. These characters resonate with audiences because they reflect common human experiences and emotions. Examples include Bilbo Baggins from “The Hobbit” or Jim Halpert from “The Office,” who represent relatable individuals navigating challenges that test their character.

10. The Innocent

The Innocent archetype is often characterized by a sense of purity, optimism, and an unwavering belief in the goodness of humanity. This archetype can be traced back to various cultural narratives and mythologies throughout history. For instance, in literature, characters like Dorothy from “The Wizard of Oz” exemplify the Innocent’s quest for happiness and safety in a world that can often be harsh and unpredictable. The Innocent seeks new beginnings, embodying hope and the potential for renewal.

Historically, this archetype has been represented in religious contexts as well; figures such as children or saints often embody innocence and purity. In Christianity, for example, children are seen as pure beings who possess an innate connection to divinity. This perspective reinforces the idea that innocence is not just a personal trait but also a spiritual state.

However, the Innocent can also exhibit naivety or an overly trusting nature. This aspect is evident in many fairy tales where characters are deceived due to their inability to recognize malice or danger. The tension between optimism and realism creates a rich narrative space where the Innocent must navigate challenges that test their beliefs about goodness.

11. The Sage

The Sage archetype symbolizes wisdom, knowledge-seeking, and introspection. Historically, figures embodying the Sage archetype can be found across various cultures and epochs. For instance, in Ancient Greece, philosophers like Socrates and Plato epitomized the pursuit of truth through dialogue and rational inquiry. Their teachings emphasized the importance of self-examination and understanding one’s own ignorance as a pathway to wisdom.

Sages pursue truth through learning and understanding while guiding others with their insights. This role is not limited to ancient philosophers; it extends to modern-day educators, scientists, and thought leaders who dedicate their lives to uncovering knowledge and sharing it with society. The Enlightenment period in Europe saw an explosion of intellectual thought where Sages like Voltaire and Rousseau challenged existing norms and encouraged critical thinking.

However, there is a cautionary aspect to the Sage archetype: they might become detached if they focus too much on intellect over emotion. This detachment can lead to a lack of empathy or an inability to connect with others on a personal level. Historical examples include some renowned scientists who, despite their groundbreaking discoveries, struggled with interpersonal relationships due to their intense focus on intellectual pursuits.

12. The Explorer

The Explorer archetype embodies curiosity, adventure, and a desire for discovery that has been pivotal throughout human history. Historically, figures such as Marco Polo and Christopher Columbus exemplify the Explorer archetype. Marco Polo’s travels along the Silk Road introduced Europeans to Asian cultures, goods, and ideas, significantly impacting trade and cultural exchange. Similarly, Christopher Columbus’s voyages across the Atlantic Ocean opened up the Americas to European exploration and colonization. Modern examples of Explorers might be astronauts and lone travelers.

Explorers push boundaries—not just geographically but also intellectually and culturally—to find their place in the world. They value freedom highly; however, this quest can lead them into struggles with commitment or feelings of restlessness when faced with routine or limitations. In psychology, this behavior aligns with traits associated with high openness to experience—a personality dimension linked to creativity and a willingness to embrace novel ideas.

Literature has long celebrated explorers as heroes; think of characters like Odysseus from Homer’s “The Odyssey”, whose journey symbolizes not only physical exploration but also personal growth through challenges faced along the way. Yet this relentless pursuit can come at a cost: explorers may find themselves isolated from those who do not share their adventurous spirit or face internal conflicts stemming from an inability to settle down.

If you enjoyed this article, you should definitely try the JUNGIAN ARCHETYPES TEST